Without doubt, Queensland’s lesser-known Cape Melville National Park is one of Australia’s most remarkable coastal destinations for adventurous and self-reliant campers.

Tucked away in a remote far-flung corner of eastern Cape York, the park’s rugged and diverse landscapes stretch 70km from the Jeannie River northwards to the glistening waters of Bathurst Bay.

The eastern section of Bathurst Bay offers wonderful beach camping in a singularly spectacular setting, excellent fishing and encompasses land and seascapes that are superbly rich in both natural and cultural history.

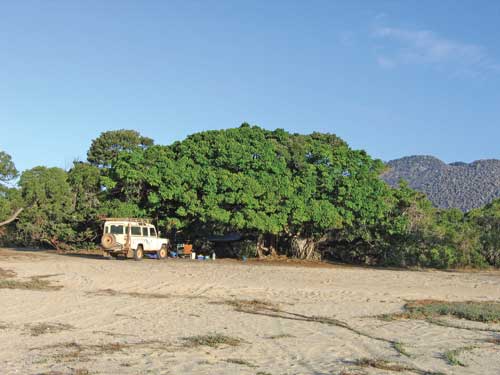

The long sprawling beach of the bay is dotted with groves of ancient gnarly wongai trees, which provide excellent shade from the tropical sun and picture postcard views out across the northwest Coral Sea.

Behind the beach lies an imposing mountain range composed entirely of jumbled giant granite boulders, officially termed the ‘boulder field’.

These rocks formed 120 million years ago when molten magma solidified underground and was exposed over time as the surrounding landscape weathered and eroded away.

There is no shortage of camping spots.

Upon arrival at the wonderful vista of the beach, your first options are to either swing westwards towards Dead Dog Creek or eastwards before being blocked by another small tidal stream.

However, many more campsites are available even further east of this creek.

To access, return to where the main track first hits the beach, cross back over the small salt pan then immediately turn left and follow the eastward running track.

En route, you’ll cross a magnificent small jungle-clad stream that slowly contracts back as the dry season progresses.

Later in the year, follow a diverging track upstream to where water can be drawn from the crystal-clear boulder pools at the base of the range.

Bathurst Bay’s iconic wongai trees are only known from Cape York and produce an edible fruit with a taste similar to a date.

This traditional food for the Indigenous tribe of the area – the Yiithuwarra (or saltwater) people – is also a staple for Torres Strait pigeons migrating southward from New Guinea to northern Australia during their annual summer breeding sojourn.

A plethora of marine wildlife can typically be observed from the beach, often without even leaving your camp.

Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins, green turtles, flocks of terns and white-bellied sea eagles regularly patrol the inshore waters, while sightings of dugong and estuarine crocodiles swimming by are not uncommon.

Occasionally, huge Queensland gropers will venture into the clear shallows and, with care, it is also possible to show children the gently flapping stingrays that are visible in most of the small creek mouths around low tide.

While a boat is definitely not necessary to enjoy the magic of Bathurst Bay, in suitable weather a seaworthy dinghy will allow you to venture out to the nearby islands, reefs and estuaries for some excellent tropical fishing.

The Great Barrier Reef comes closer to the coast at Cape Melville than it does anywhere else in Queensland, and its presence is signalled by Pipon Island and its fringing reef, only 5km across the channel from Cape Melville.

Around the local reefs, it’s possible to capture tropical delicacies such as coral trout, red emperor and sweetlip.

Land-based anglers can target the equally tasty grunter, mangrove jack, trevally, Cooktown salmon and the evergreen favourite… barramundi.

The sandy beaches are also decorated with thousands of small shells, which will keep curious people busy for hours as they search out the more attractive specimens.

Few Australians know that Bathurst Bay was the site of the country’s worst maritime disaster outside of war.

In early March 1899, an intense tropical cyclone swept in from the Coral Sea and decimated a large pearling fleet that was anchored at the bay.

Remarkably, Queensland’s only meteorologist of the time – the colourful Clement Wragge – predicted the cyclone’s development from far off Brisbane, over 2000km away, with only the most basic of weather observations.

Tragically, there was no way to warn the unsuspected pearling fleet that was annihilated by Tropical Cyclone Mahina’s swift approach.

Mahina thrashed the area – 370 mariners were known to have perished, along with an undetermined number of Aboriginal people on the mainland.

The cyclone generated a 12m high storm surge that swept up to 5km inland, stranding large numbers of fish, porpoises, sea snakes and dugong.

One schooner, the Silvery Wave, managed to somehow stay afloat.

As the cyclone’s eye passed over, Captain Jefferson measured a barometric pressure of 26” – about 880hPa – the lowest ever recorded in the southern hemisphere.

From the few stories of survival, perhaps the most remarkable is of the two couples who swam 16km from Howick Reef to the mainland after their vessel sank.

A marble monument to the cyclone victims was erected about 600m inland against the eastern end of the Melville Range, the position of the access track marked by a stone cairn on the beach.

Visitors may also find wreckage of an American air force Dakota plane that crash landed on the beach in 1945 after running out of fuel.

A number of the planes’ 22 occupants parachuted out prior to the beach landing, one of whom was never seen again.

The rest of the crew and passengers were subsequently rescued.

The Melville Range boasts a number of wildlife species that are found nowhere else in the world, apparently a result of the areas’ unique environmental conditions.

This includes three unique species – the Cape Melville boulderfrog cophixalus petrophilus, the Cape Melville shadeskink saproscincus saltus and the Cape Melville leaf-tailed gecko saltuarius eximius.

However, the list also includes one plant, which has gained a place in Australia’s more recent history.

The endemic foxtail palm wodyetia bifurcata is a handsome and hardy species that naturally grows only in among the rugged boulders of the Melville Range.

Discovered by western science in the 1970s, this attractive palm soon became the target of illegal poachers, who cut tracks through the dense bushland to gain access to the palms and received up to $5 a seed on the worldwide black market.

These smuggling activities were eventually stamped out by an intensive long-term bush surveillance operation by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service rangers and Queensland Police, in an effort that became a unique part of Australia’s conservation history.

The main palm areas are on the inaccessible southern and western end of the range.

However, some can be sighted from a distance by crossing over the spring-fed creek at the base of the range and gazing southeast towards the top of the boulder field.

Local conditions, logistics and getting there

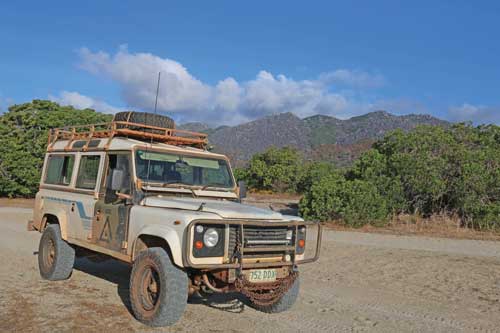

Becoming completely isolated during the summer monsoon season, Cape Melville National Park is accessible by four-wheel-drive and only during the tropical dry from August to November.

The downside of the area can be the blustery southeasterly trade wind that sweeps the area with astounding ferocity – we’ve had steaks blown off our plates!

Frankly, if the forecast wind speed is 25 knots or more, a visit to Cape Melville is going to be a misery.

It makes plain sense to wait for better weather, if possible.

Taking good care of this special place is essential.

All rubbish should be taken out, soap should not be used in the pristine spring stream and cutting into the iconic wongai trees, or any other tree, is an absolute no no!

Burying fish frames, even high up on the beach, is dangerous because it will attract crocodiles sniffing out a free feed and endanger campers.

The presence of crocodiles and marine stingers makes swimming in the sea hazardous, with the cool boulder pools of the spring creek offering a much safer and refreshing way to cool off!

There is no ranger base on the park – the rangers work their extensive area by 4WD and swagging it across the landscape.

Bathurst Bay can be accessed from Cooktown via the 220km long Starcke Coast, which is 10-12 hours, or via Laura, about 210km and 5-6 hours.

It is essential to be totally self-sufficient, and these townships provide the last opportunity to replenish fuel and food supplies.

Adequate freshwater should be carried at all times while travelling and supplies can be topped up at the stream at Bathurst Bay or at another small spring stream on the main road 20km south of the bay – these being the only permanent supplies available year-round.

Beware that the soft sandy stretches may require the lowering of tyre air pressure.

It is recommended that travellers carry an air compressor for re-inflating tyres, the usual 4WD recovery gear, good sand pegs for holding tarps and tents for if it does get blowy and either a reliable satellite phone or high frequency radio for emergency communication with the outside world.

This is an ideal fair dinkum bush destination for well-prepared families and others with an adventurous bent.

The necessary camping permits for this magic natural place can be obtained online from the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service website – qpws.usedirect.com/QPWS/

Happy and safe travels!

Bush ‘n Beach Fishing Magazine Location reports & tips for fishing, boating, camping, kayaking, 4WDing in Queensland and Northern NSW

Bush ‘n Beach Fishing Magazine Location reports & tips for fishing, boating, camping, kayaking, 4WDing in Queensland and Northern NSW