IT’S been a while since we had one of these little chats, Fred.

The first time was almost 30 years ago when we discussed beach driving techniques in the Tide Guide. Last time was last year when we looked at some of the peculiarities of tides. This time I thought we might check out how the moon affects fishing.

But before we do, let me make very clear that I am not a gun fisher. I never have been. I have met plenty of fishers who say they are. You’ve probably met them too, Fred. A mate of mine has a nickname for such blokes: Motor Mouth. Their mouths never close as they tell you how good they are. In all my years (I’ve accumulated a few), most people who I have found to be experts would never claim to be. I should clarify now that those who write magazine articles offering fishing tips they have learnt over the years, especially for their particular region and in their area of expertise, are not self-proclaimed experts.

They’ve been asked to write because of their recognised talent and are happy to pass on their knowledge. You would be hard pressed to find one who boasts. Experts can often be recognised as those who return from a trip with the biggest catch (most times) and then modestly tell you how lucky they were, not how good they were. Any chance to fish with them is a privilege and an education. When you fish with them, they would never tell you the way you were fishing might be wrong. They would kindly say you have a fishing style different to theirs. When you are sitting out there with them and they have been bringing in lots of fish and you haven’t would be when to ask them why.

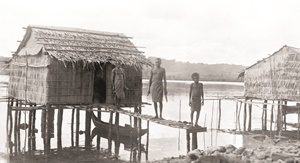

My first encounter with an expert that I clearly remember was in the January school holidays after my first year at school. I was about five years old and sitting on a ramshackle jetty poking out over the sand flats into a king tide in the Mooloolah River, about where Sea Life Sunshine Coast (Underwater World) is today. I was trying for sand whiting by hand lining green string wrapped around a stick with a small hook and piece of worm. Sadly, I wasn’t having any luck. The water was as clear as the air and I could see the fish hunting around the jetty piles and nuzzling the sand below me. I was getting bites but no fish.

A small Aboriginal girl from my class at school was watching my failures from the shore. After about 15 minutes, she came up beside me and shyly asked if she could try. I gave her the line. Within a minute, she had brought up an elbow-slapper. She took the hook out of the whiting’s mouth and politely handed the fish to me. “Here you go,” she said. I was a clumsy kid. The fish went straight through my fingers, straight through the slats of the jetty and straight into the briny.

She gave me the line. “You can catch it this time,” she said. Her confidence in me wasn’t justified. After another 10 minutes of nothing, I gave her back the line and asked her to show me how she did it. Again, within a minute, she had brought up another elbow-slapper. Even though I was watching and expecting it, and she was telling me what she was doing, I never did understand how she managed it. But this time I told her that as she had caught the fish, she should keep it. I wasn’t being a gentleman. I couldn’t risk further embarrassment of dropping it again.

I’ve met quite a few quiet experts over the years, Fred. About 25 years ago, when delivering Tide Guides well down the coast a long, long way south of Brisbane, I met an old bloke who was probably then a decade or two younger than I am now. He suggested I consider publishing a book that told anglers the best times to go fishing, based on where the moon was in its lunar month (which is roughly 29.5 days) adjusted to suit our yearly calendar, and where it was in the sky on any given day. He went on to explain that the old fishos in his district always fished by the moon and told me the basic rule.

I was a bit rude – I laughed at him. I had tried the American John Alden Knight’s Solunar Tables on numerous occasions, always without success. So I told him I thought the lunar theory was for lunatics and I would keep fishing the tides, thank you. He clammed up. I should have remembered my motor mouth before I opened it in front of him. I should also have remembered that the moon is what gives us our tides every day.

A couple of days later on the same delivery trip, I struck another, older fisher with a similar story. Fred, I had finally learnt my lesson. This time I shut up and listened politely but I still didn’t take him seriously. I’m not saying I’m a bit thick, Fred, but it wasn’t until the third encounter that I finally started wondering if there might be some truth hidden in those claims.

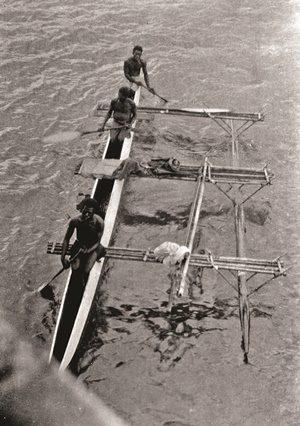

The third encounter was with a fifth-generation professional fisher whose family had kept detailed records of their catches from the early days of Australia’s settlement. He showed me just enough to spark serious interest. My background is newspaper journalism, Fred. Researching and checking facts was and still is part of the job. The long drive home from that delivery trip kept me occupied thinking about where best to find reliable, qualified information that might substantiate or disprove the lunar/solar claims of the older fishers.

In those days, though Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had not long started on their way to becoming billionaires through their fledgling personal computer company Apple, though Microsoft was still a year or so away from releasing Windows for IBM PCs and clones, a very basic form of internet was available to those who could hook a business computer up to a copper landline telephone, type in several lines of complex code and try to link into the databases of those universities and libraries around the world that had begun to invest in online access for external users. One mistyped character in those strings of commands would result in failure.

Research by internet 30 years ago was a tedious, error-prone process, Fred. My long nights of searching (some overseas libraries were open only in their local business hours) did bring up the titles of potential research material. From there, it was a matter of accessing the printed material. That meant daily visits to libraries, asking for various titles to be obtained for me to skim through, rejecting most but occasionally striking documents with potential.

The more I read, the more intrigued I became. Every night I would bring back to base a thick bundle of photocopied pages, to be read and filed in specific categories. Next day I would go back for more. That was how the Angler’s Almanac was born. It doesn’t have all the answers. It deliberately withholds some information. But it does explain to its readers how they can work out part of the predictions themselves. All they need is a working knowledge of celestial and coastal navigation: celestial for aspects of astronomy; coastal for aspects of tidal influences.

A few copycats have since published their own predictions as a result. Within a year of the Almanac’s release, calls were coming in from throughout Australia and overseas. Most were positive, including one caller from America who didn’t want to identify himself but did want me to tell him why the Angler’s Almanac worked in Australia and the American Solunar Tables did not. Naturally, Fred, I didn’t tell them. I’m sure they would have worked out for themselves long ago why the Almanac will work anywhere in the world with the correct adjustments for the differing ‘local times’.

I’m sure they have adjusted their own predictions to do the same. Theirs was a simple mistake, easy to make. Then again, Fred, perhaps they haven’t. I just looked them up on the internet a few minutes ago and they show only a map of North America and its time zone adjustments. We produced a similar map for our Angler’s Almanac app a few years ago when we released it internationally, along with the rest of the Americas, Africa, the UK, Europe and Asia.

Don’t ask why we discontinued the app. The answer would be long and boring. Believe me, the book is better value for everyone.

Fred, I don’t have the space here to give you a full rundown on the Angler’s Almanac in one article. If you want more, ring the editor and ask him to hound me for more. Meantime, here’s a little ditty that might give you a clue why the Almanac works:

“When the moon is high;

In the eastern sky;

Tho’ all the world might sleep;

Now is the time to wet a line;

And reap the bounty of the deep.

But remember, Fred, just because the Almanac’s predictions say the fishing should be great on a particular day at a particular time doesn’t mean you’ll catch lots of fish if you go fishing then, so don’t be disappointed when you don’t. Don’t blame the book. Far more factors are involved than just having a baited line in the water at the predicted time. We’ll discuss them later. Meantime, have a think about the bloke who rang to complain that the Almanac’s predicted best times always coincided with low tide at his favourite fishing spot, which was a comfortable rock surrounded by water only at high tide.

He never caught many fish there but it was his favourite fishing place. I politely suggested that about half an hour before the book said he should be fishing, he should take a camping chair out over the sand flats to a channel that always had water in it when the tide was out, plonk his bum on his chair and try his luck there. Strewth, Fred. He actually rang me back a fortnight later to thank me.

Next issue we’ll talk about empty tummies on a full moon.

Peter Layton

Peter is the publisher of the Tide Guide and Angler’s Almanac.

Bush ‘n Beach Fishing Magazine Location reports & tips for fishing, boating, camping, kayaking, 4WDing in Queensland and Northern NSW

Bush ‘n Beach Fishing Magazine Location reports & tips for fishing, boating, camping, kayaking, 4WDing in Queensland and Northern NSW