By the time trout cod were identified as a species in Australia, they were almost extinct.

But, according to renowned fish ecologist Associate Professor Mark Lintermans, thanks to decades of conservation efforts, they are on the verge of being upgraded from endangered to vulnerable.

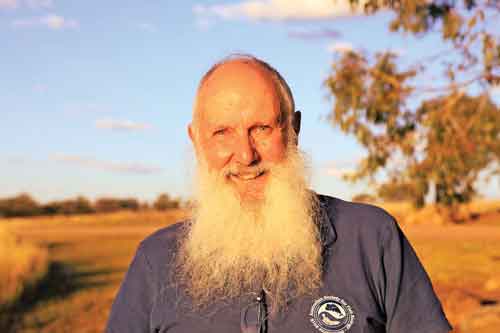

University of Canberra’s Centre for Applied Water Science, Freshwater Fisheries Ecology and Management, Assoc Prof Lintermans has been at the forefront of native fish protection and habitat restoration for more than 30 years.

Up until about half a century ago, trout cod were not even identified as a separate species to Murray cod.

They are currently listed as endangered, and anyone who catches one must immediately release it back into the water with minimal harm or face heavy fines.

As part of an extended interview with OzCast – the official podcast of OzFish Unlimited, Australia’s fishing conservation charity – Assoc Prof Lintermans said, “They are a species that was so misunderstood.”

“Trout cod was described as a separate species in 1972 and since then there’s been another two cod species described.

“We have four freshwater cod in Australia – they’re all threatened.

“A fish is a fish to a whole lot of people’s eyes, and they don’t understand the subtle differences.

“Murray cod are a yellow-green colour with coarser mottling and trout cod are this bluey-grey speckled colour.

“By the time they were recognised as a separate species, they were in deep trouble and we’ve been pedalling as fast as we can to try and recover them.”

In the 1800s and early 1900s there were commercial fisheries all through the Murray Darling Basin, so huge amounts of fish were going to markets for food after being caught in totally unsustainable ways.

Trout cod disappeared altogether from several rivers in Victoria, NSW and around Canberra in the 1970s.

“They’re a great angling species, a bit more aggressive than Murray cod,” Assoc Prof Lintermans said.

“If you had the two cod species in one location and you flicked a lure out, trout cod would hit it first and hard.

“People loved to fish for them.

“Back in those days, fish were a limitless resource.

“There were millions of them in the water, so you’d just catch them hand over fist, and that didn’t do them any favours.

“They tend to occur in slightly faster and deeper water and they’re slightly more aggressive, so the remaining isolated populations got hammered harder by recreational fishers, but it was habitat loss and alien fishes that are mostly responsible for their decline.”

The major factor that has helped their partial recovery and upward trajectory is that they breed well in captivity, with as many as 40,000 eggs produced by single female trout cod.

“We’ve been going at it for 30 years, but I think they’ve improved in conservation status,” Assoc Prof Lintermans said.

“They’re still listed as endangered, though we did a review about three years ago and we reckon they have improved to ‘vulnerable’.

“With trout cod, we started re-introducing populations into small creeks and we would put about 400 fish in a stream.

“All of these re-introduction efforts are a numbers game – it’s about how many fish you can put in and how long you can do it for.”

Assoc Prof Lintermans has worked extensively with OzFish and other community groups and government agencies in habitat restoration, which is crucial to ensuring methods such as restocking waterways for threatened fish to have a better chance of success.

Stocking on its own is not enough, with a project in the Ovens River in northeastern Victoria where about 30,000 trout cod were stocked annually for a decade highlighting how it’s not a sure-fire solution.

“In that 10-year stocking program, there were only two where the stockings did really well,” Assoc Prof Lintermans said.

“What you’ve got to do is keep things going for a length of time, so you can hit the good years when the flows and temperature are just right and you’re in the ‘Goldilocks’ zone – everything is just right and your stocking takes.

“If you did it for only two years and they were bad years, then you’ve missed out, you’ve failed.

“It’s about perseverance, it’s about bloody-minded people who just want to keep going.”

There’s often an outcry when a native animal becomes extinct, though Assoc Prof Lintermans said aquatic species don’t get the same kind of attention as their land-based counterparts.

“We have no freshwater fish known to have become extinct in Australia,” he said.

“We probably lost some before we knew they were species.

“It’s currently estimated that we’ve described only two thirds of our freshwater fish.

“Some of them we sort of think we know what they are.

“The majority of those are small bodied.”

Some people argue that animals that are endangered should be left to become extinct because they’re not tough enough.

“Well, I don’t think that’s right, otherwise you’d just let everything go,” Assoc Prof Lintermans said.

“You could kiss koalas goodbye for starters.

“You say that to people and they’d be up in arms.

“If a fish goes extinct, they’re probably a little more relaxed about it.”

The delicate balance between fish and survival hinges upon the restoration of vital habitats.

As the plight of threatened fish echoes through Australia’s rivers and streams, the urgency becomes ever more apparent.

By embracing the call to action, we hold the power to rejuvenate these aquatic ecosystems, ensuring the continuity of both the intricate biodiversity they harbour and the stories they whisper for generations to come.

With Mark Lintermans and other dedicated people fighting the good fight for Australia’s native fish, their chances of survival are on the rise, particularly with the backing of organisations such as OzFish.

Mark Lintermans is considered a leading expert in freshwater ecology and fish conservation in Australia.

The second edition of his book Fishes of the Murray-Darling Basin was released recently.

Paul Suttor

OzFish Unlimited

Bush ‘n Beach Fishing Magazine Location reports & tips for fishing, boating, camping, kayaking, 4WDing in Queensland and Northern NSW

Bush ‘n Beach Fishing Magazine Location reports & tips for fishing, boating, camping, kayaking, 4WDing in Queensland and Northern NSW

In the Murrumbidgee for every murray cod caught you catch 10 x bluenose (trout cod). They are certainly not endangered in the ‘bidgee. Locals claim the bluenose are a natural food for the larger murray cod and in the last decade there has been a tipping in the balance of carp/bluenose and murray cod as the number of bluenose has increased due to stocking programs.

Purely as a result of stocking. Not wild fish. And probably not self-sustaining, once the stockings stop.

It is profoundly misleading to claim trout cod “weren’t even recognised as a separate species until 1972”.

Indigenous people knew trout cod were a separate species to Murray cod for millennia. And by the mid to late 1800s, many observant amateur and commercial fishermen were well aware that trout cod were a separate to Murray cod. And in the early 1900s, NSW Fisheries’ own Chief Naturalist D.G. Stead recognised trout cod were a separate species based on clear biological differences, including a vastly smaller size at first sexual maturity in trout cod. Stead also published a major newspaper article (available on TROVE) on trout cod in 1927.

For a decade or two the various state and territory fishery departments happily accepted Stead’s advice that trout cod existed and were a separate species to Murray cod. For example, you can look at gazetted fishing regulations from NSW and the ACT in the 1910s and 1920s that include trout cod and list regulations for trout cod separate to those for Murray cod.

But, then we had some pathetic attempts by incompetent ichthyologists in the 1930s to claim this wasn’t so, and some alien-trout-obsessed fisheries agencies for whom it was also convenient to claim there was only one cod species.

A far more honest and accurate way to describe the situation would be to to say that it was well-recognised that trout cod existed and were a separate species to Murray cod, but that some incompetent ichthyologists and alien-trout-obsessed fishery agencies preferred to insist there was only one species of cod … for non-scientific, vested-interest reasons … until blood serum and protein research in 1972 forced them to admit there were two cod species. And that’s after they deliberately ignored some earlier research in the early 1950s by T.C. Roughley, also using blood serums, that also showed trout cod were a separate species to Murray cod … and deliberately ignored all Stead’s research and conclusive biological evidence from the early 1900s.

A big issue with the current efforts with trout cod recovery is that they pretend trout cod are primarily a lowland native fish and their decline is supposedly all about timber snag removals in alluvial lowland rivers. This is absolute rubbish, and is a convenient false narrative driven by trout-obsessed fishery agencies to suit their trout-and-trout-stocking-at-all-costs management.

In fact, historical and biological research shows extremely clearly — beyond dispute — that the trout cod are primarily an montane/upland native fish, and their primary habitats were montane/upland rivers and streams … including some surprisingly small streams … and to some surprising (montane) altitudes … and that their loss from every such habitat was the invasion and domination of these habitats by alien trout … reinforced by constant saturation stockings of alien trout. Trout cod shared these montane/upland river and stream habitats with Macquarie perch, which, surprise surprise, are also almost entirely lost from these habitats because of alien trout domination and constant alien trout stocking, and which, surprise surprise, also isn’t acknowledged, and which are also misrepresented at midland/lowland fish.

(NB: the publicly available Sustainable Rivers Audits 1 & 2 show this clearly and ALSO SHOW that many of these montane/upland river and stream habitats are in excellent condition and that habitat degradation and dams are NOT an explanation for the disappearance of trout cod and Macquarie perch from them.)

As for the damage of alien trout and alien trout stockings upon these native fish: even today, we’ve had past small trout cod stockings in the Upper Murrumbidgee and current small trout cod stockings in the Lower Goodradigbee being deliberately sabotaged by huge annual stockings of predatory alien trout. It’s completely unacceptable. And we still mass-release predatory alien-trout in endangered Macquarie perch habitats of the Upper Murrumbidgee River. When are these clearly unacceptable and frankly, disgusting, practices going to stop?

These are just some of the issues that the current “accepted” approach to trout cod recovery (and Macquarie perch recovery) continually dance around and refuse to acknowledge.

Also, we actually do know of several native freshwater fish species lost to extinction.

This include:

— the Macquarie perch species endemic to the Shoalhaven River system

— the eastern cod species once endemic to the Brisbane River system

— a number of Galaxias species in south-eastern Australia, which have been extirpated by alien trout (details in

Raadik 2014)