HOW often in life can you say you get something for nothing?

There aren’t many places you can go or many things you can do that won’t cost you something. In fact, I used to think the only way I could move my canoe from A to B without any cost except the sweat off my brow was with a paddle. Turns out I was wrong, thanks to free power from the sun and a trusty electric outboard! While electric drives on canoes and kayaks have been around for quite a long time, they have traditionally suffered from short battery life, requiring large-capacity and very heavy batteries to cover any reasonable distance.

Typically, a 100Ah battery (weighing 30kg-plus) when paired with a 40lb-thrust motor may have pushed your canoe for 10-15km if you were careful. While this was OK, it did somewhat limit your day on the water. Similarly, solar power is no new thing. However, recent innovations in the engineering of solar cell performance and control of the power they generate has meant modern panels are lighter, more efficient and more robust than ever before. The power output from a moderately sized (1sq m) solar panel is enough to recharge an average sized (50-80Ah) battery in a day.

Meaning that in theory the same canoe and motor configuration we discussed above, if fitted with a solar panel and allowed to charge for a short period in the middle of the day, could do almost twice the distance with a much smaller battery. That’s a lot less sweat off your brow and certainly worth some investigation! Just how much sweat will my brow be losing though? Being the dedicated man of science I am, I decided we needed more facts regarding the performance of electric and solar-powered canoes and so, set about rigorous testing over the recent Christmas break.

We came up with some very interesting results. Before I go into detail, I’ll start with a brief overview of what we hoped to achieve and how we set about doing it. We felt that to make an electric outboard a viable proposition on a canoe it needed to achieve two criteria. It needed to have a run time that would provide a reasonable day on the water and it needed to be light and compact enough to not interfere with the day’s activities. It also had to be cost effective, otherwise why not just get a tinnie!?

The setup we envisioned to make this work was a canoe and outrigger fitted with a 40lb thrust electric motor, 1sq m flexi solar panel and 55Ah gel battery. Our thinking was this combination would be light weight, easy to attach to a variety of different craft and provide a good compromise between run time and overall system cost. As the power output for solar cells was already known and well documented, we focused our attention on determining what battery power would be drawn for different canoe sizes and configurations.

We tested a range of canoes from 11’ to 16’, with and without outriggers and at a range of motoring speeds. To ensure we achieved maximum possible speed from the canoes being tested, we used a 60lb-thrust motor and 100Ah battery. Our theory being, once we worked out power draw for a canoe configuration, we could then work backwards to determine what size motor would best suit. Testing was then a simple matter of motoring a canoe over a set route through the range of speed settings on the motor.

At the end of each run a reading would be recorded for average speed, battery voltage and current drawn. From this we were able to plot power versus speed, determine battery life and the theoretical distance that configuration could travel. The testing was done at Logan day use area on Wivenhoe Dam on a very still, and very hot, Boxing Day (after all, the Aussies were getting annihilated in the cricket) in an area unaffected by wind or current. Here’s some of the interesting things we discovered along the way.

Size of canoe had very little effect on speed achieved and power drawn. The longer canoes went a little faster and drew a little more power, but not that much. Using an outrigger made very little change to speed or power. Extra weight in the boat made little change to speed or power. Again, as expected, more weight meant more power drawn, but not that much.

The thing that had the greatest effect on speed was depth and trim of the outboard. We found that setting the motor height as close to the surface as practical gave the best speed results. The outboard shaft is the biggest drag on the system and spending a bit of time optimising the height will have a dramatic effect on travel distance for your canoe. I also suspect modifying the shaft to be more streamlined would have a significant effect as well.

So, our results in a nutshell.

Average top speed for a canoe between 11’ and 16’ is about 7.5km/h. At this speed you could expect to travel about 13km on a 100Ah battery (using 60 percent battery power). If you want maximum distance, reduce the speed to 4km/h and you’ll get closer to 20km. Slow and steady definitely wins the race. The slower you go, the further you are able to travel, which is great news for trolling fishers and people without small children who need to travel quickly to reach the next toilet break. The max power drawn in most cases was less than 430W (36A), which means a 40lb motor would be a suitable choice for all but a very heavily laden canoe.

Please note: we based all our distance calculations on only using 60 percent of battery power (60 percent depth of discharge). It is possible to go to 80 percent, however a corresponding reduction in battery cycles (number of recharges) could be expected. If you’re not concerned about battery life (you don’t use the battery that often, for instance), then dropping to 80 percent DOD sometimes would be OK. More expensive lithium-ion batteries are able to drop to 90 percent DOD and would be worth considering for regular long-distance motoring.

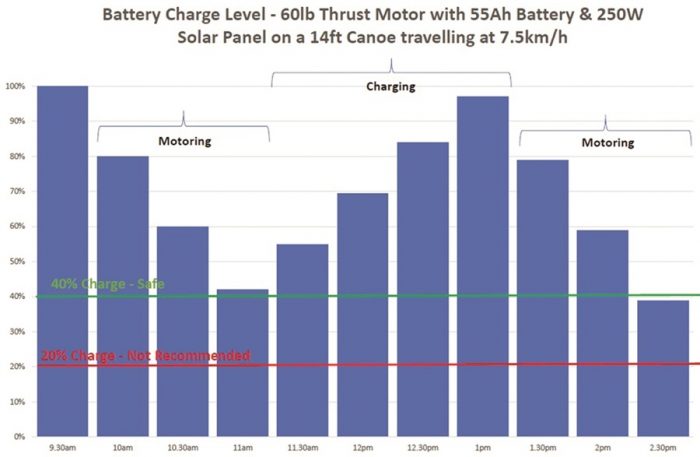

So back to our original idea of solar-powered canoeing, what could a day on the water look like with a solar/battery combination? Here’s an example case study using a 14’ canoe fitted with an outrigger, 40lb-thrust motor and 55Ah gel battery with 250W solar panel. Our party leaves at 9.30am and motors out on the lake to their favourite swimming spot. If we have a 100Ah battery on board, that can only be 6.5km away, otherwise we are paddling home. With a 55Ah battery and 250W solar panel, it can be 11km away. Our battery will be down to 60 percent DOD, but we have the sun to recharge it.

We are assuming it’s Easter in southeast Queensland and the solar efficiency is about 77 percent. We are also allowing for the panel to be mounted flat in between the outrigger poles with no tilting towards the sun. After two hours of swimming and eating lunch we have a recharged battery and are ready to head home.With a fully recharged battery and the afternoon’s sunshine we have enough battery power to motor 11km back again to our launch site without ever having to put a paddle in the water.

Paddle manufacturers of the world are right now calling for my immediate whipping! The outcome is 22km travelled over the course of a six-hour day and not one drop of sweat on your brow, not even from having to lift the battery out of the canoe! The added bonus to this system is cost. Our proposed combination of 40lb-thrust motor, 55Ah gel battery and 250W flexi solar cell could all be purchased for less than $750. When you consider you never have to buy fuel, that’s pretty good economics.

It turns out some things in life can come for free!

To find out more about testing of canoes with electric drives, feel free to give me a call at One Tree Canoe Company on 0424 001 646 or visit onetreecanoe.com

Happy paddling/motoring.

To read more about One Tree Canoe Company’s range, click here!

Bush ‘n Beach Fishing Magazine Location reports & tips for fishing, boating, camping, kayaking, 4WDing in Queensland and Northern NSW

Bush ‘n Beach Fishing Magazine Location reports & tips for fishing, boating, camping, kayaking, 4WDing in Queensland and Northern NSW